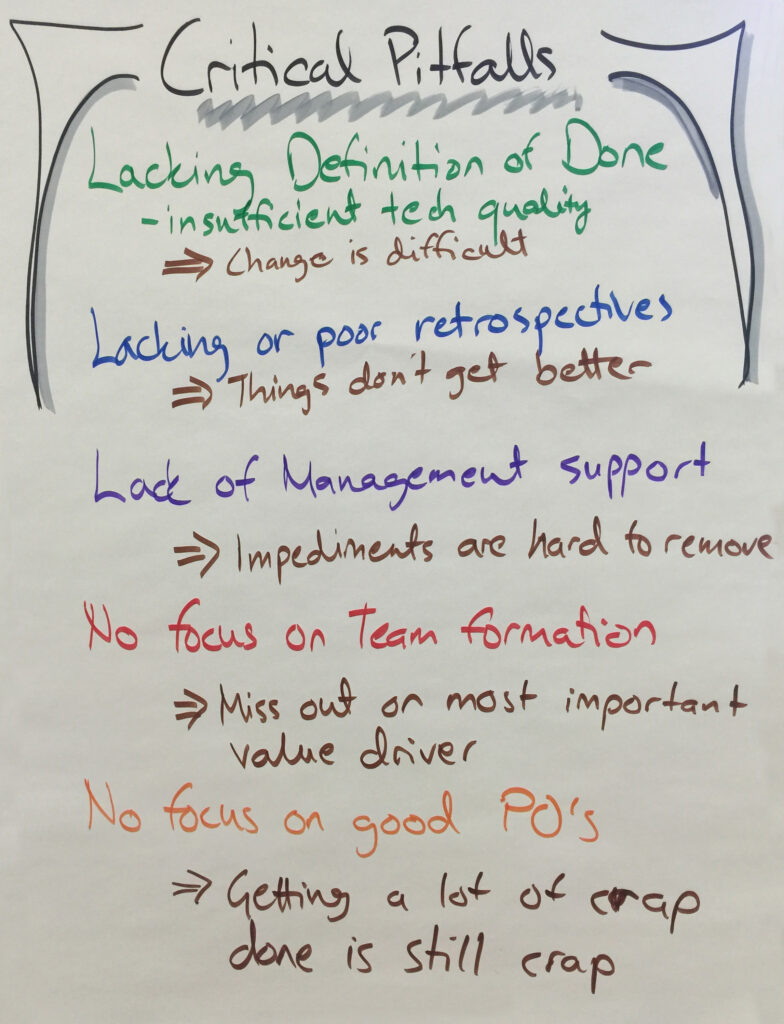

The Five Big Pitfalls in Using Scrum

The list already says more than 54 words. There's 55. But they imply much more than their measly number. Let's put a little depth into the 5 critical pitfalls.

Lacking Definition of Done

Scrum is silent on technical practices, simply because it's a work management framework and agnostic to the context. But that doesn't mean the the technical level doesn't matter. Imagine putting Kimi Räikkönen to drive a Lada, will he perform well in a race?

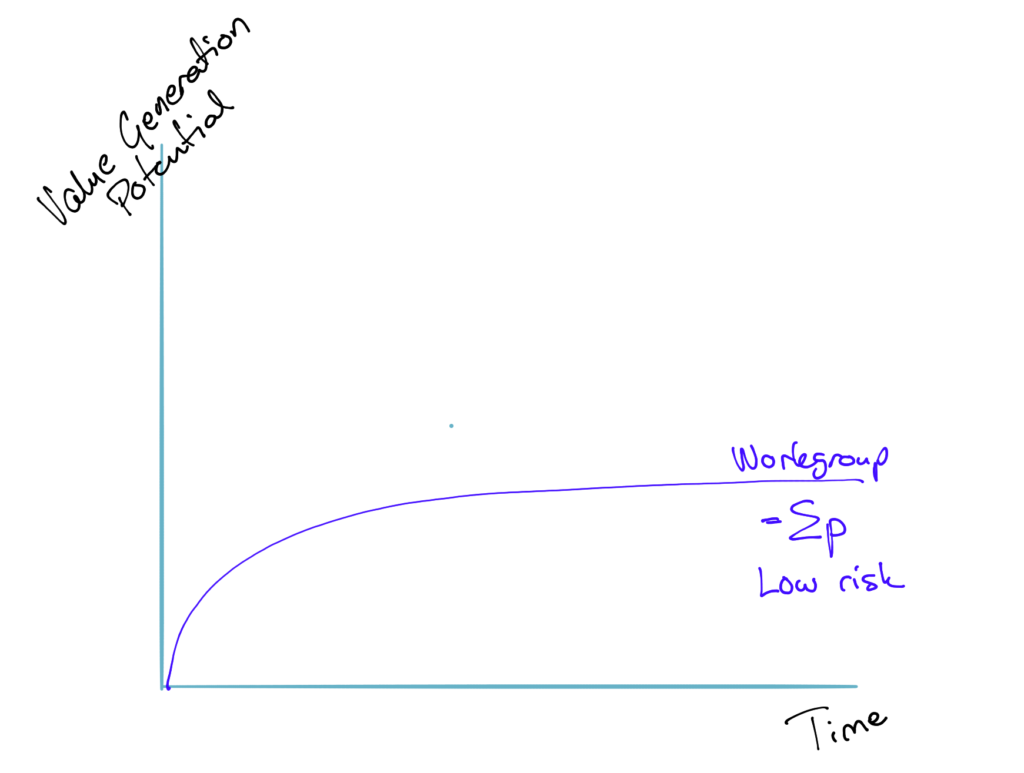

For a Scrum to really take off and work, the team has to at least be able to complete a working version of the product at the end of the Sprint. That's the absolute minimum. It should be better than that, really. Ideally, at the end of every single small modification. The working increment is a confirmation that whatever the team tried to do is working and enables us to actually eliminate the technical risk associated with that change. The smaller the timeframe, the smaller the risk.