Why might we choose a team approach?

In the first blog I compared two primary approaches for group coordination – workgroup and team. I also tried to emphasize that the two are both valid approaches (I’m assuming everyone understands that a bad workgroup is not a good approach). So when might we choose one or the other?

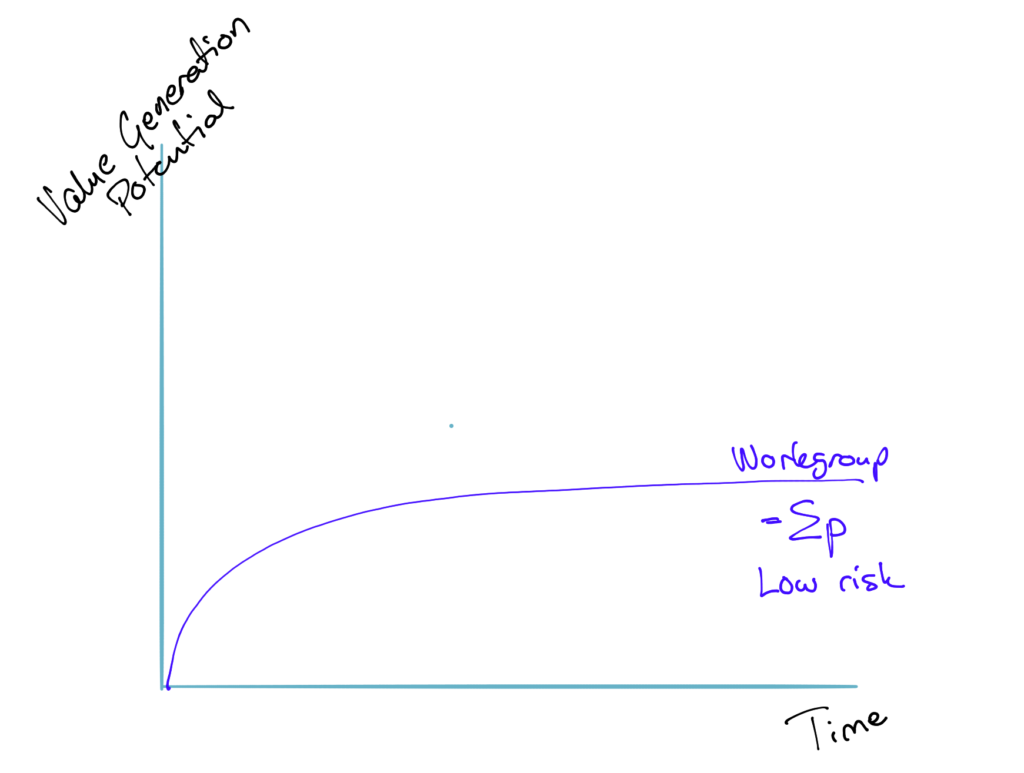

We can see the most important difference in the graphs below. On the X-axis we have time. On the Y-axis we have “value generation potential”, which is really a terrible way to say how awesome they can get.

Pros and Cons of Workgroup

In the first graph, to the right, I have the workgroup. The great thing about a workgroup is that it’s easy to set up and get started. As long as we know who the people are and what they can do, the leader can quickly assign them to tasks and things start getting done. It’s also easy to delegate things further to other people. The main drawback is that the potential of the team is limited to the sum of the members individual abilities (including the leadership ability of the leader).

Another benefit is that workgroups are of low risk – both emotionally and organizationally (is that a word?). Since our focus is on our tasks, we can easily avoid conflict and just say, “I’m just doing my work”. That doesn’t mean, of course, that we wouldn’t ever have conflict in a workgroup, but that we can deflect the worst of it if we wish to. We still can care a lot about the tasks we do, and passionately defend them :).

One more benefit is the fact that workgroups have ways to deal with larger groups and partial allocation. Surely, those conditions do impact the overall effectiveness of the team, but workgroups are not crippled by them.

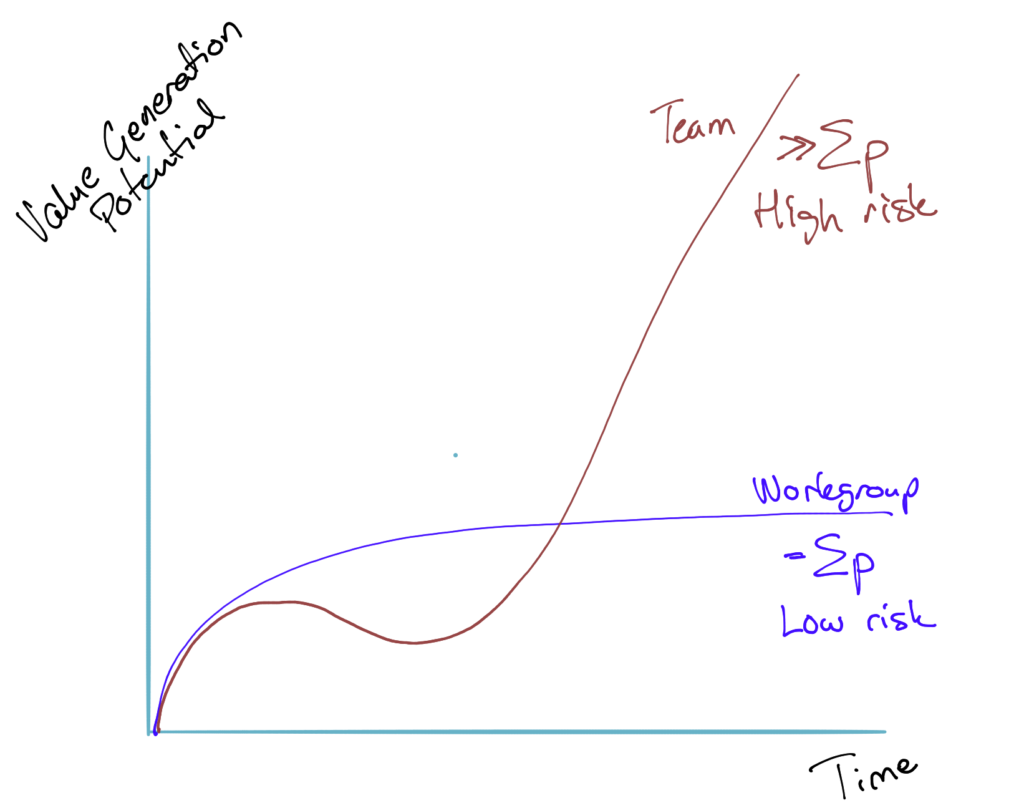

Pros and Cons of Teamwork

In the second graph, I added the team’s line. As you can see, the very beginning of a team is like in a workgroup. People avoid conflict as they are not clear on what we to do, who the other people are, and what their role is in the group. But at some point, the members start voicing questions, concerns and opinions. It is at this point that the lines really diverge.

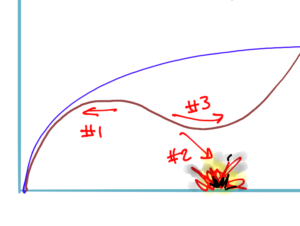

Because of the emerging conflict, the team loses some of its ability to get things done. Also the leader and their plan are often challenged. At this point, three things can happen.

#1 is that the leader, or someone within the team sometimes, feels uncomfortable with the challenge and seeks to prevent the conflict, effectively trying to push the group back to the workgroup line.

#2 is that the conflict gets out of hand, and the group is either disbanded, members removed, or people leave themselves.

Obviously, what we would like to see is #3 – finding a way through the the conflict and turn it into a source of innovation and improvement. When this happens, the team rapidly improves they operation and, if this goes long enough, can turn into a powerhouse.

The downside is that this process is very risky. Since being in a team requires that all members commit to a shared goal, it’s not possible to become a team without strong emotional connections between the people and goals. We may not be ready for that, or it might be simply unsafe to do so. Accepting and embracing conflict isn’t easy, nor are the necessary behavioral changes we must accept during the process. The reward, if we get to it, is great – teams can be tens, if not hundreds, of times more effective and deliver results that are not possible any other way. It’s also emotionally very rewarding, and people get life-long relationships and great pride for the achievements they reach.

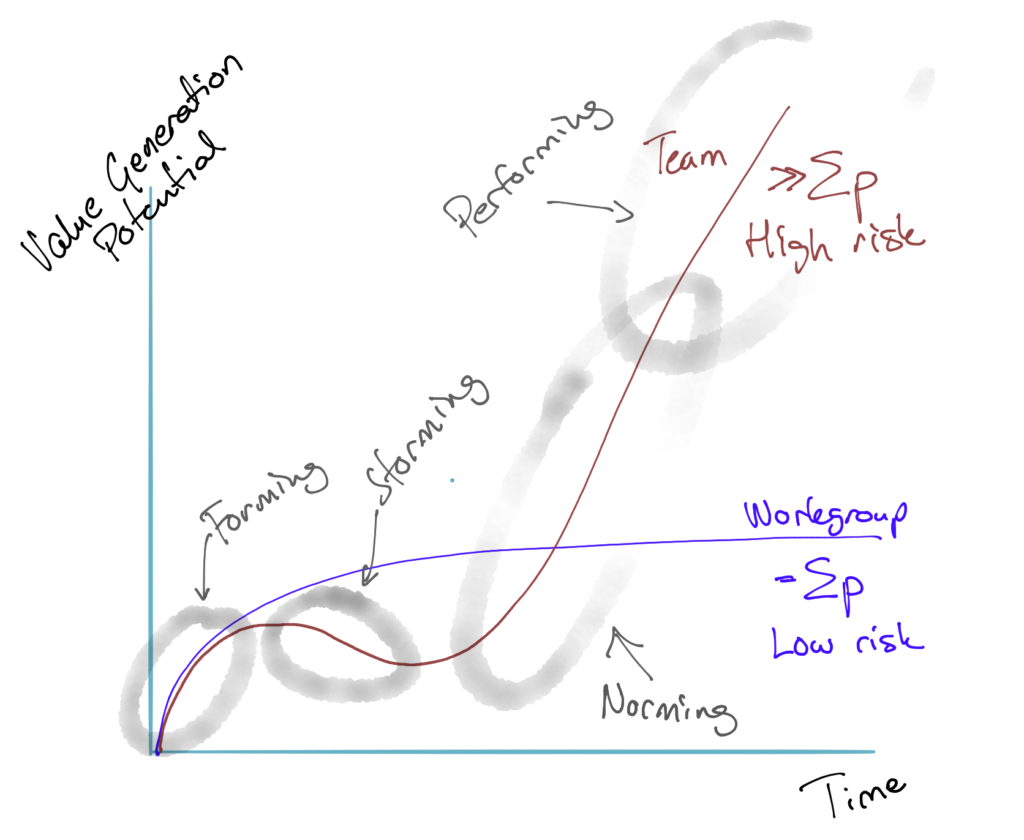

If you’ve studied teams in any way ever, you probably see the classic Tuckman stages on the graph. I’ve spelled them out in the diagram to the right.

A lot of books focus their attention to the four states, but personally, I think the critical points in this growth path are the transitions from one state to another. By seeking to understand what conditions are needed to move forward, we can establish a “pull” approach instead of trying to “push” the team formation. We will explore that idea, and the states, more in a subsequent post.

The Choice

So basically, the workgroup approach is good when you know quite well what to do and there’s really no big challenge or need for major innovation. We get good people, coordinate well, and win. Going for a team approach is probably taking on too much risk.

When that is not enough, i.e. we are facing significant uncertainty or big challenges, we best go for a team. OR, when we want to intentionally tap into the reservoir of value potential to access something greater than “the normal”.

But I want to come back to something I started this blog with – neither of those approach is bad. There are a lot of situations where a good workgroup well executed can get the job done. When we go for a team, we should know what we are doing, because a failed team can cause lots of damage and even emotional harm to people.

In the next chapters I will start talking about my views how to be more successful with team formation.